WARNING: I’m a bit rambly here, which is understandable after spending three days in Maine staring at the ocean, which IMO does wonders in stirring up your sub-/unconscious…

I posted this Note the other day:

It floated up after an intense concentrated morning of work on my memoir where I realized that I’ve been so focused on the matrilineal parts of my genealogy that I’ve totally neglected the patrilineal side.

And oh boy, did I find some surprises, like that it was my mother’s father who taught her how to sell discarded [or stolen ;-)] items in order to earn a few pennies during the Depression, and that perhaps it was his never-naturalized citizenship that caused his wife to banish him to living in a separate room — or in a chicken coop — and taking his meals outside, away from the rest of the family.

And that when it came to her own marriage, my mother did the same thing, only instead of banishing her husband from her house she banished herself by moving into the den and spending most of her waking hours there, away not only from him but from me and my sister.

I know, I know, all hypotheticals, but what is a memoir but taking your memories and the facts that you know and spinning them into some interpretation that can only ever answer your own questions, and to hell with anyone else’s?

Strange truths can bubble up when you go spelunking in the murky depths of your own consciousness and history…but I’m getting ahead of myself.

Maybe this is why I’ve been struggling with the memoir…I’ve been so focused on trying to remember what happened that each memory and event is siloed off in its own neat compartment, which is especially true when I write each event on its own individual Post-It, each color-coded for childhood, early adulthood, and present adulthood.

I’ve never been able to envision the flow of the memoir from beginning to end, partly because I’ve been trained in my writing career to think of everything as separate: the specific points I want to make in an article, and/or the chapters in a book where events and chronology are the most important thing and not the story itself.

It’s all been vertical. And it’s been my big block in moving forward. For years I’ve used the Save the Cat [mostly vertical IMO] outline as gospel, employing magical thinking that it would save me from the hard [horizontal] work.

Same when it comes to my piano. I was borderline prodigy when I was a kid and could sightread almost anything put in front of me at tempo…except for Liszt. Too many notes. ;-) Somehow I intuited that in order to do this I had to look at the next measure while I was playing the previous one…of course, this is TOTALLY vertical. It also meant that not only did I not fully focus on what was in the present — the measure I was playing — but that in order to keep impressing the adults around me — the only time anyone paid attention to me — I had to rely on the vertical, if that makes sense.

The point is that the melody is horizontal but the underlying accompaniment can be primarily vertical, at least in piano and organ music where there’s so much going on, with secondary voices to bring out, pedaling, dynamics, etc. etc., so that the vertical chunks have always pretty much been all I can see…just like in my books.

For instance, I’ve been working on this movement lately.

Uchida tells a story, start to finish, while I tend to focus not only on each measure but also on getting the notes right while also remembering to not bang on the keys to not stress my nerve-damaged hands along with a million others things with the result that I end up looking at each tree — actually, each leaf — and not the forest.

After all, the piano is an orchestra unto itself.

I mentioned my dilemma to a friend who’s also a pianist, and she offered to listen to me play to see if she hears it as chopped up. That would be helpful, but even if she told me that the music flowed, I would still hear it in my head as chopped up, each measure standing alone.

I’ve also struggled with feeling the music because when I was a kid it was all about the pyrotechnics: the faster, the flashier, the better. As I have progressed on going deeper in my memoir I’ve gotten better at feeling the music when I’m playing. And I will admit to using a mental cheat sheet, particularly when it comes to Schubert: I think about his sad life and the fact that he lived with the knowledge that he was going to die a very young death. I am able to hear that in the notes of one of his sonatas or impromptus. And definitely in his string quartets where angry indignant bow strokes in the last movement of Death and the Maiden is nothing but him shaking his fist.

When I travel I always like to find a piano to practice on, and this week I found a piano in the sanctuary of a local church. I ended up taking a lesson with the organist and music director and asked him how to make everything more horizontal so I could achieve more of a line in the music.

His advice was so terribly simple: Play as softly as possible. That will slow everything way down so that you can hear the lines and phrasing while also reducing tension in your arms and hands.

I tried it and honestly, it was a miracle. The horizontal floated up naturally. The tension was gone. I can honestly say it was the best piano lesson that I’ve ever had…and I’ve had thousands.

It then occurred to me that this was also great advice for my memoir, which I’ve been trying to write like my previous vertical books. So going forward I will try this: Go soft, slow down, don’t force anything. Maybe, just maybe, the story will naturally reveal itself.

What a revelation.

This Week’s Takeaway: Insanity is defined as doing the same damn thing over and over and over again, and being surprised when things don’t change. If you’ve been struggling with an issue in your work or life for months or years, how about doing the opposite? For instance, if you normally write fast, try to write slow, or by hand if you always write on the computer. If you fall too easily into fights with a particular person, try to be the opposite of how you are with them. It’s definitely worth a shot.

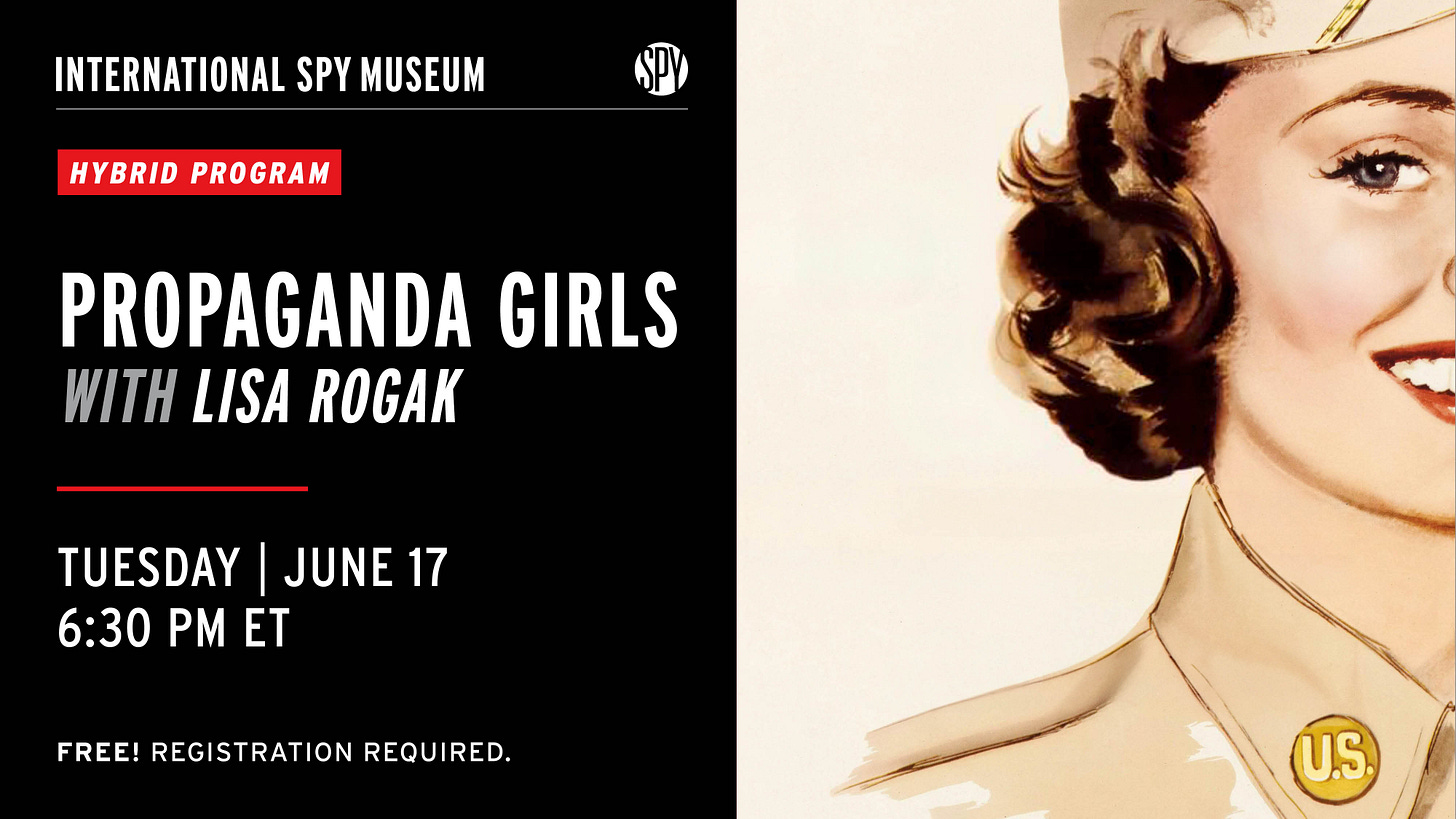

This Tuesday, I’ll be speaking about Propaganda Girls at the International Spy Museum. You can register to attend either in-person or online here.

Great post this week, Lisa, although you might give yourself more credit for your tendency to stick to the vertical: it's really a different philosophy of the writer's (journalist's) relationship to the subject being written about, and an effort to steer as clear as possible away from molding truth into a pleasurable story -- and by "pleasurable" I don't mean a happy story necessarily but one that pleases both the writer and reader in its form, its satisfying tying of loose ends, its precise editing out of non sequiturs and ambiguities that don't easily fit into the overarching tale. Lives are complicated and humans' actions don't necessarily gel into a single streamlined trajectory of causes. This is where the analogy of playing a piece of music (which is already written by someone else) to writing a narrative about a life or lives might fall apart: the emotional arc, the editing, and the thematic cohesion have been pre-made, by and large, for the performer of a finished piece (leaving room for the nuance of individual performances, of course), whereas for the writer of non-fictional lives there's a different sort of care involved in respecting the truthiness of verticality and research-based journalism while also understanding the need to tell a particular and engaging and meaningful story on the basis of all that research and all those fragmented facts. And with a memoir it's also a function of accepting that what you write is as much about you, and your desire for cohesion and coherence, as it is about the family members you're trying to document and understand.

In today's NY Times there's a very thoughtful essay by Parul Sehgal on the genre of biography which resonates a bit with the vertical/horizontal opposition you describe. A passage of particular interest: “'The effort to come close,' [as Joyce's biographer Richard] Ellmann puts it, 'to make out of apparently haphazard circumstances a plotted circle, to know another person who has lived as well as we know a character in fiction, and better than we know ourselves, is not frivolous. It may even be, for reader as for writer, an essential part of experience.'

"Why is that?...The subterranean drama of the biography, as the critic and practitioner Janet Malcolm has written, is provided by the biographer’s own motives and masks — the choices the biographer might make when confronted invariably with the gaps in the archives, the burned letters and lost diaries.... A biography is less a portrait than a record of an encounter. This 'effort to come close,' to apprehend, is what we track, what gives the life its pulse. Biography may be built on facts, but a fact, as Saul Bellow wrote, 'is a wire through which one sends a current.”

I’m a firm believer of finding the story organically.