A Simple Twist of Fate

When I first received my father's military records from his service as a Navy medic during World War II, it took several years to open the envelope. Did I really want to know his secrets/what he had [barely] lived through when he was still a teenager, and the untreated war trauma that I believe contributed to his death at the age of fifty in 1974?

I skimmed the papers a couple of times but never dug too deep. I knew there’d be a line in the sand: Now you don’t know, but now you do.But with the 80th anniversary of V-J Day looming — August 14, 15, or September 2 depending upon who you ask and which country you’re in — I decided to brave the Pandora's box.

What I found on the surface: A Purple Heart’s twisty route, test scores on early exams, all ships and bases he’d set foot on even for less than 24 hours, and countless blank pages — researchers at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis are nothing but thorough. Also two charges of desertion, one of which resulted in a ten-day sentence of solitary confinement and rations. But nothing told me what he had experienced during the doldrums of service as well as the duress of battle and bombardment against an enemy whose dictate to fight to the death may as well have been tattooed on their arms.

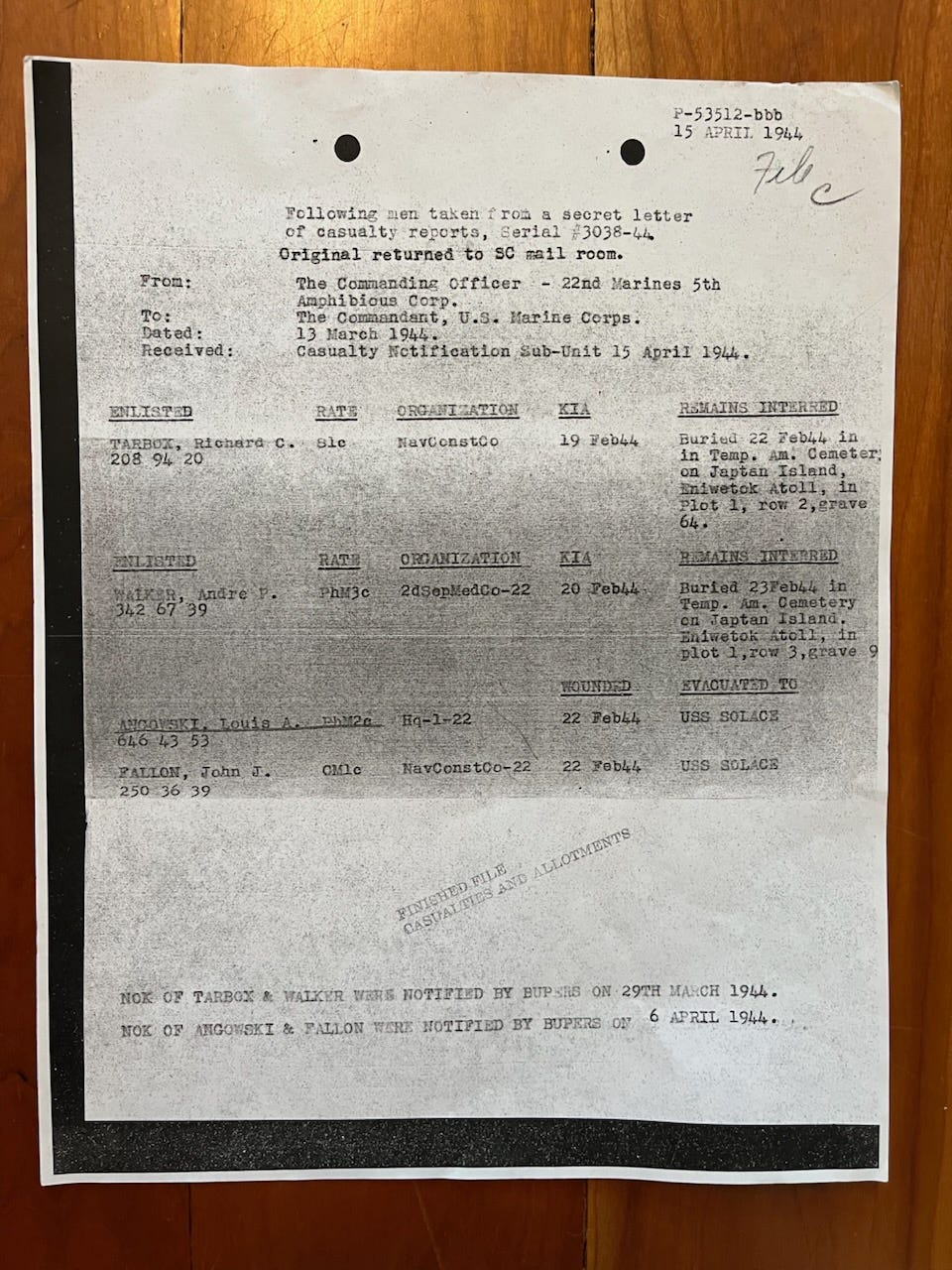

When I saw the document above I froze, each of four names on the copy-of-a-copy splayed across the paper like a tombstone.

TARBOX, Richard C. KIA 19 Feb44

WALKER, Andre P. KIA 20 Feb44

ANGOWSKI, Louis A. WOUNDED 22 Feb44

FALLON, John J. WOUNDED 22 Feb44

A record of casualty transport. Two alive — including my father, ANGOWSKI, Louis A. — two dead.

All four men were involved in the battle of Eniwetok, part of the epic battle for the Marshall Islands in February 1944.

What I knew and felt about my father’s experience and trauma was so distant to me; to look at it directly would be like staring directly at the sun. But I was drawn to the three other names on the memo; maybe they’d serve as my training wheels. So I started digging, and asked for help from Beth Reuschel, a military researcher who specializes in finding information about veterans from World War Two through the Vietnam War. What she uncovered was poignant and surprising.

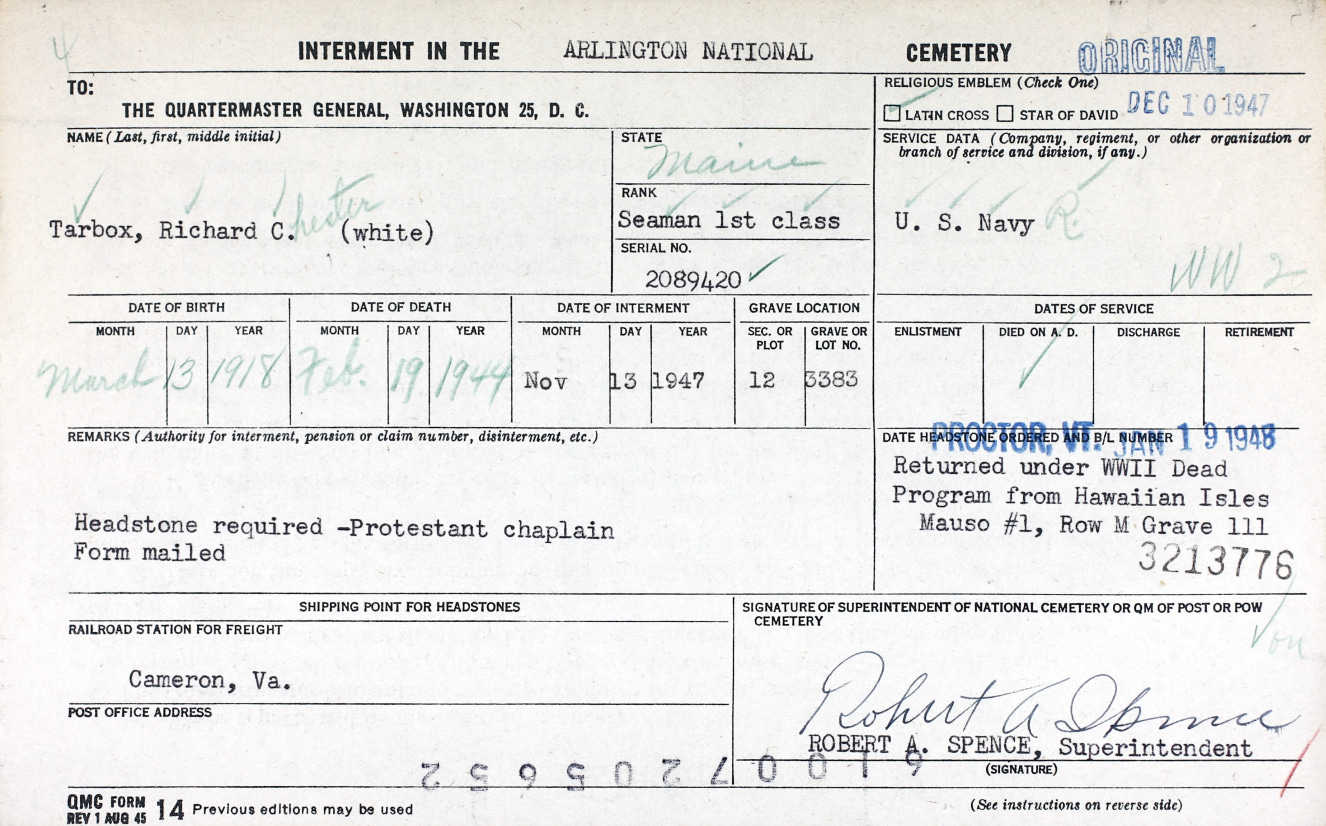

First up: Richard C. Tarbox from Hallowell, Maine. KIA. Without his military file — which would take months to arrive — information was scant. But between Newspapers.com, Ancestry.com, and Beth’s own secret channels, a few documents did pop up.

Beth found a photo from a 1943 edition of the Portland Press Herald with his photo, along with other Mainers on their way to basic training.

From enlistment to interment…pretty harsh, but that’s all we could find. According to the interment records, his body was moved twice, once from Eniwetok to Hawaii, and then to Arlington National Cemetery, almost four years after his death.

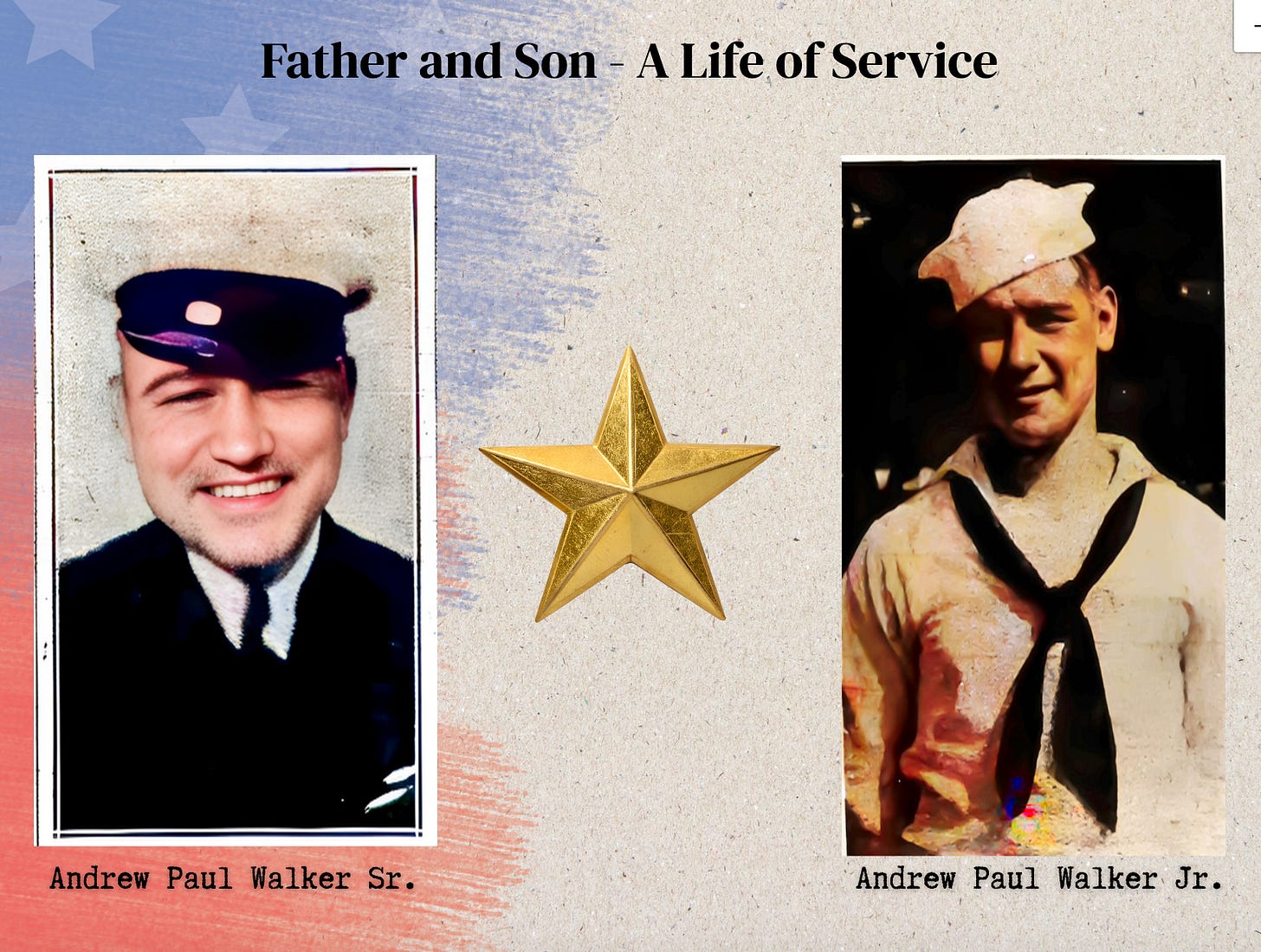

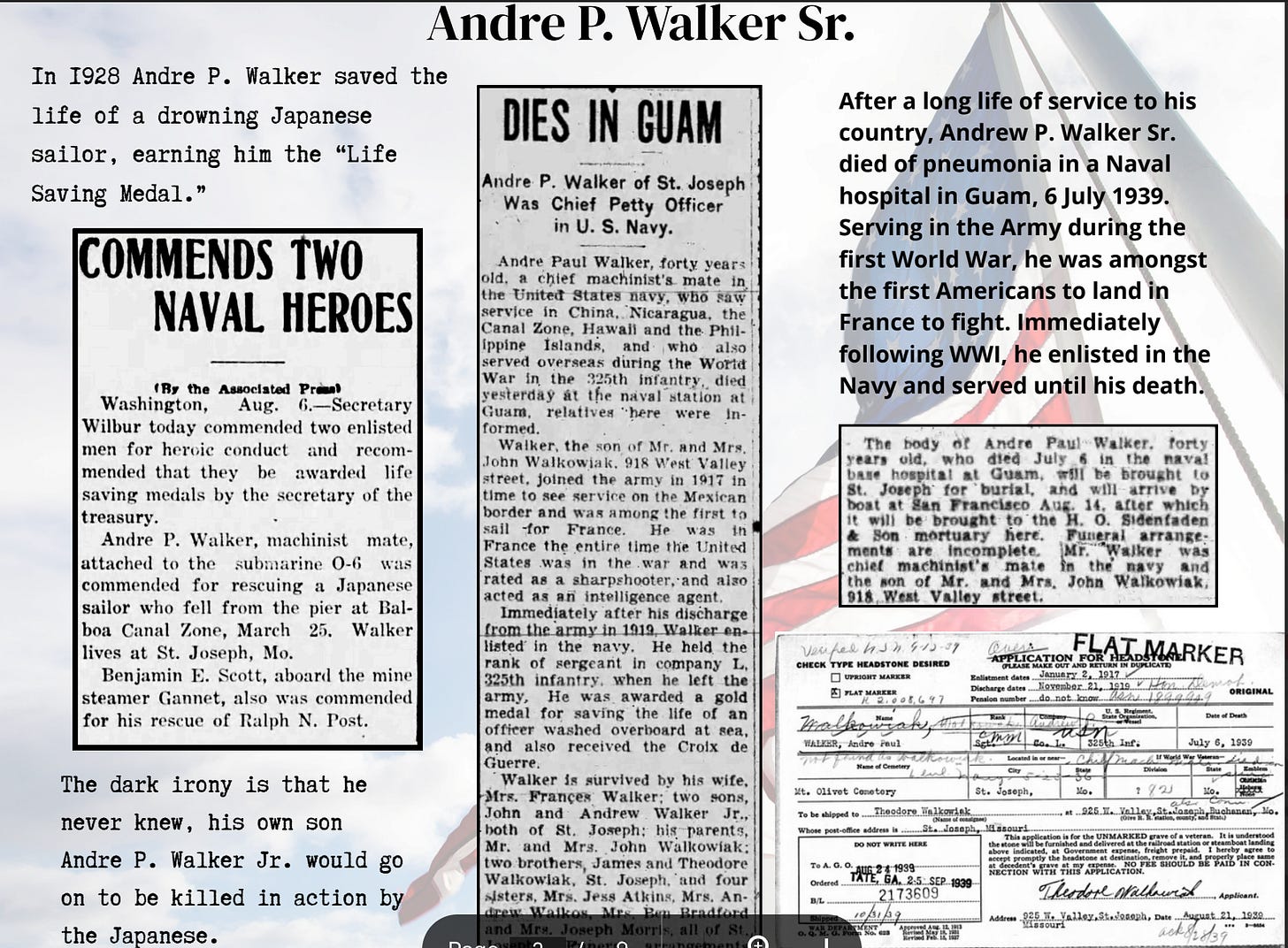

Next, Andre P. Walker, Jr. Andre P. Walker Sr. — his father — was a career military man and had received a medal for saving the life of a Japanese man in 1928. The great irony: a Japanese soldier killed his son.

A newspaper clipping captured the somber quiet of the two minutes of silence that St. Joseph, Mo. held for Andre Jr. and two other men as their bodies returned home.

All I could think is this “reverence” for fallen military would be a rare occurrence in today’s world, and many people would be bitching at the inconvenience for one reason or another… Many drivers don’t even pull over for emergency vehicles any more.

Interestingly, both men were from Maine and their deaths were mentioned in the same article in the Evening Express on April 18, 1944, though Walker’s mother — Andre Sr.’s widow — had apparently moved to St. Joseph, Missouri, between the time of his death and when she received his body. She had also remarried at some point — probably after her husband’s death in 1939 — and was now known as Mrs. Cynthia Ladd.

Admittedly, even with the scant information, it’s a lot to process.

My father’s inclusion on that casualty list? I view it as an infinitesimal twist of fate. If the bullet had landed a fraction of a millimeter to the right, then I wouldn’t be here.

Of course, we all love to play these what if games — What if I had swiped right instead of left? What if I had stayed home instead of going to that party? — but sometimes the What If? is indeed a matter of life and death.

Next week: The ones who came home.

This Week’s Takeaway: Research often takes a circuitous route, and sometimes you have to look at other people in order to learn about those who you are researching. For one, your defenses are down but often you’re able to extrapolate more, similar to researching the neighbors of your ancestors in a 100-year-old census record. Your mind can fill in the blanks more easily. Plus, it hurts less that way.

The awful thing about Eniwetok is that unlike many amphibious assaults, the beach was difficult and raked with machine gun fire. I wasn't there of course but it rivals the Omaha beach in its immediate and startling casualty rate.